The Story of Fr. Stanley Rother

In the early 1960s, Pope St. John XXIII asked churches in North America to aid the people of Central America. The Dioceses of Oklahoma City and Tulsa established a mission in Guatemala, and soon one man from Okarche, Oklahoma answered the call, finding himself in Santiago Atitlán, a poor village in the Central American country.

That man’s name was Stanley Rother; he was a priest and a member of Catholic Order of Foresters. He belonged to Holy Trinity Parish and Holy Trinity 1816, Okarche, Okla.1 Originally from Okarche, the Rev. Fr. Rother grew up on a farm, and had four younger siblings.

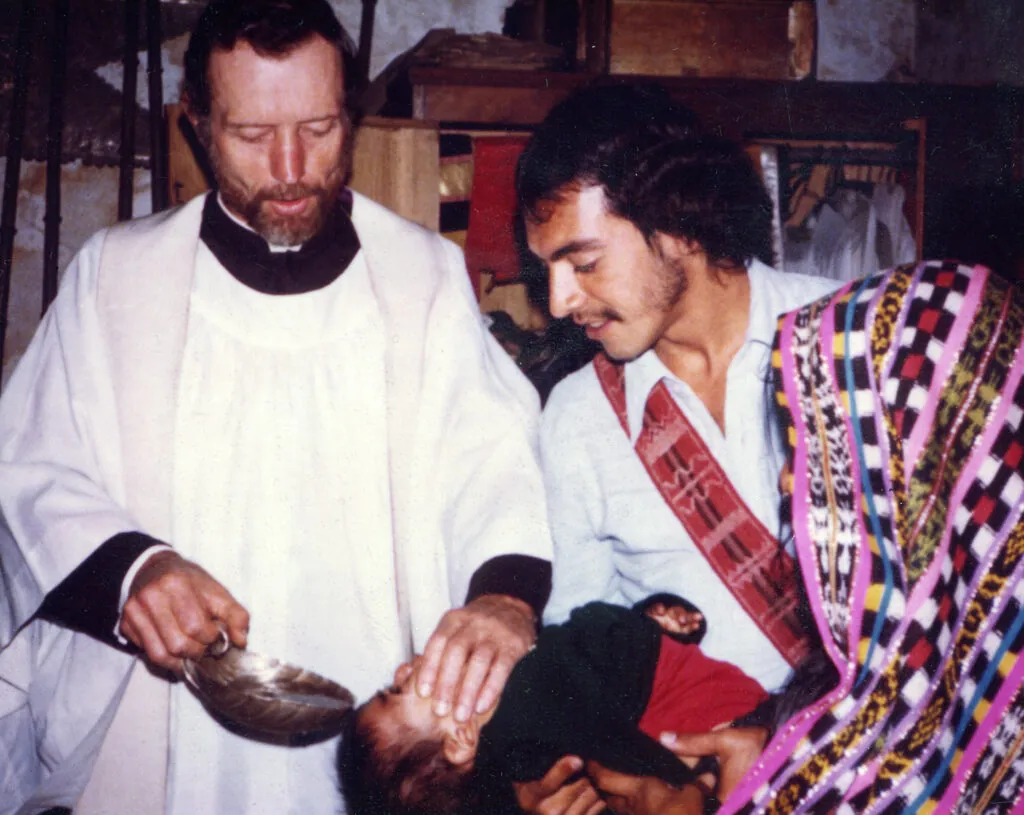

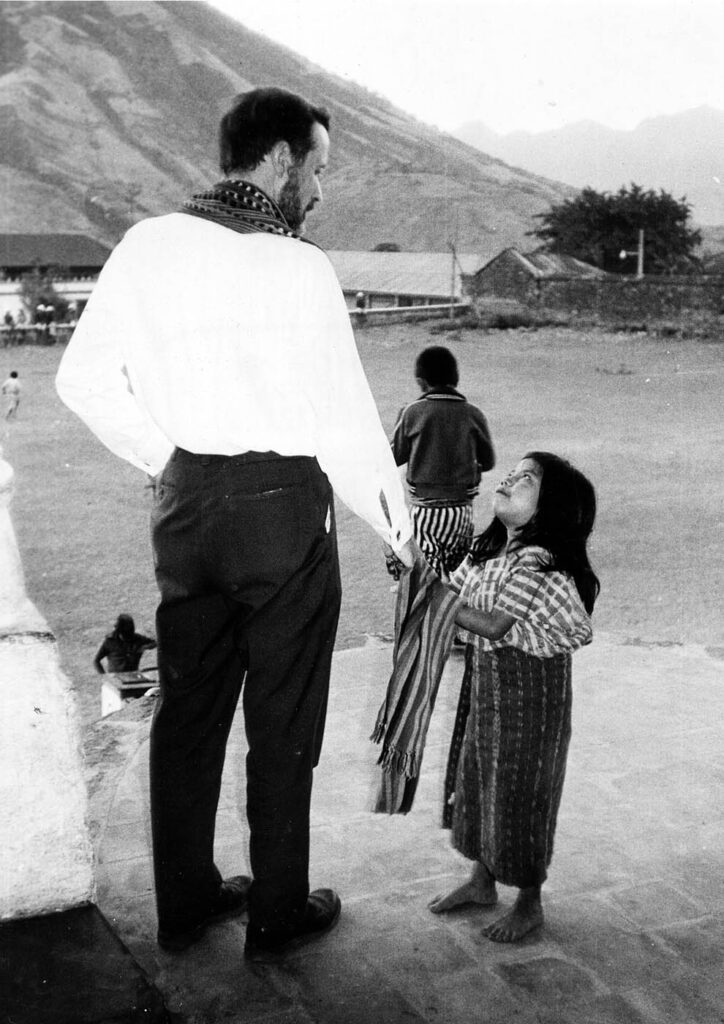

In Guatemala, he served the parish of Santiago Apóstol. Fr. Rother was so devoted to his work — and his people — that he learned Spanish and Tzututjil, the indigenous language. The people called him Padre Aplas, his middle name (Francis) translated to Tzututjil. Most Reverend Eusebius Beltran, Archbishop Emeritus of Oklahoma City, explained that Fr. Rother said Mass in the native language, which was something priests before him couldn’t do.

“He was a critical driving force in developing Tzututjil as a written language, which eventually led to translations of liturgy of the Mass, the Lectionary and the New Testament,” María Ruiz Scaperlanda, author of a biography about Fr. Rother, said. “Five years after he arrived in Guatemala, the same man who failed out of his first seminary because of his inability to learn Latin was able to celebrate Mass in Tzututjil for his parishioners. If that’s not from God, I don’t know what is!”

He immersed himself in the culture, adopting the clothing, eating habits and lifestyle of the locals. Fr. Rother helped develop a local Catholic radio station, a school to educate children and a medical clinic. He used his farming skills to teach people better farming techniques.

In the 1980s, the Guatemalan Civil War that began in 1960 raged on. The death threats and violence were on everyone’s mind. Fr. Rother didn’t speak much about the threats, and he didn’t let them interrupt his service.

The unstable circumstances led to people being kidnapped and killed, including more than 30 of Fr. Rother’s catechists, and often their bodies were brutally defaced. According to Oklahoma Martyr, a documentary that aired on Oklahoma Educational Television Authority (OETA) as a part of its Back in Time series, Fr. Rother would claim and recover the bodies. He did this not only to serve those who were killed, but also to serve their families, bringing them at least some relief from potentially being targeted by those same killers. He properly buried the bodies, living one of the Corporal Works of Mercy.

In the summer of 1980, Fr. Rother confided in his cousin, the Rev. Fr. Don Wolf of Oklahoma, saying if he was ever attacked in his home, he would fight until he was killed, and the attackers wouldn’t get him out of the house. “He knew it was a possibility, and he had already resolved in his mind what this would mean for him,” Fr. Wolf explained. “It was, for me, probably the most chilling thing I ever heard him say.”

In the spring of 1981 after learning they were on a kill list, four priests at the mission returned to the United States. Fr. Rother, though, stayed in Guatemala. “The shepherd must not abandon the sheep,” he said.

Soon he did come back to the United States, and he vowed his ministry would be different when he returned to Guatemala. In the few months he was home, his parents could tell his mind was elsewhere, with his people in Santiago Atitlán.

He returned to Guatemala to continue his ministry.

In the early morning hours of July 28, 1981, three sisters who lived nearby in the church heard a gunshot. They came through the house and saw that Fr. Rother had been killed.

Though no one has ever been accused of the murder, many people believe the gunmen were part of the government security forces which occupied the town.

Though his body was buried in Oklahoma, his heart remains in Guatemala — literally. Because he meant so much to the people of Santiago Atitlán and they were so dear to him, church and civil authorities permitted his heart to be interned in the floor of the church sanctuary.

In 2011, at the end of Mass on the 30th anniversary of Fr. Rother’s death, an American ambassador walked in to the church. Fr. Wolf explains, “He asks them in their native language — which is spoken by only 35,000 people worldwide — ‘Is Stanley Rother dead, or is he alive?’ The whole church responded, ‘Alive!’ It was one of the most amazing experiences of all my visits to Santiago Atitlán.”

Fr. Wolf continued, “That’s what the life of being a saint is. This person isn’t dead. They’ve stopped breathing, that’s all.”

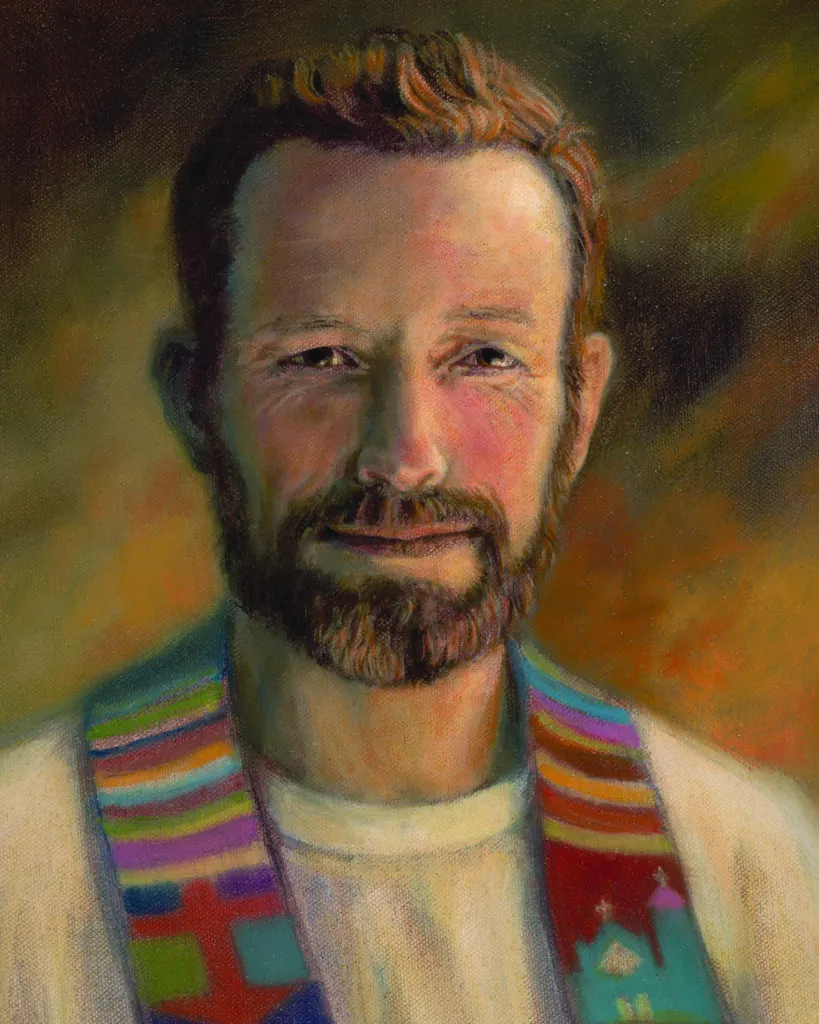

People around the world, including those in Santiago Atitlán and the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City, believe Fr. Rother is worthy of sainthood. Members of his local court believe strongly in Fr. Rother’s work, and they want to help Holy Trinity Parish promote him for sainthood. These advocates’ voices aren’t falling on deaf ears. In 2016, after 35 years of investigation, Pope Francis formally recognized Fr. Rother as a martyr. On September 23, 2017, Fr. Rother was beatified in Oklahoma City.

Now known as Blessed Stanley Rother, he is the first American-born Catholic martyr and the first American-born Catholic priest to be beatified. The next step towards sainthood is canonization, but this can’t occur until a miracle attributed to Blessed Rother is validated. According to Oklahoma Martyr, people of Santiago Atitlán experienced extraordinary things after they prayed to him. And there’s another occurrence that holds a lot of significance.

On July 3 1992, Sandra Rother, Fr. Rother’s cousin, was found not breathing. At the hospital, she received a grim prognosis. Fr. Wolf said, “She was at death’s door; they were talking organ transplants when they got her to the hospital.”

As explained in Oklahoma Martyr, she had a brain aneurism, specifically an AVM (arteriovenous malformation) hemorrhagic stroke in her cerebral cortex. As you might guess, it’s a rare condition, and only one in 10 people survives. The doctors explained the options: medication or surgery (likely leaving her in a vegetative state if she didn’t hemorrhage to death). Her parents chose surgery, and her entire family said their goodbyes. Sandra’s father called the parish priest at Holy Trinity in Okarche. The priest went to Fr. Rother’s gravesite and prayed.

And it worked. Or, he worked. Sandra survived the surgery and opened her eyes three days after.1 (If you’re familiar with Jesus’ death and Resurrection, it’s hard to attribute this length of time to coincidence.) She was released from the hospital, with no brain damage, just 77 days after she was admitted.

In early 2017 after a Mass celebrating the 100th anniversary of Holy Trinity 1816, HCR Dave Huber spoke with Tom Rother, the brother of Blessed Stanley Rother. “In my conversation with Tom, I got the sense that the Rothers were just hard working, salt of the earth people, a close-knit family with strong Catholic values.”

Though Blessed Rother isn’t physically alive today, his memory, spirit and tradition are thriving. “The sense of pride and excitement among the members of Holy Trinity is obvious and understandable,” HCR Huber, who had the opportunity to pay his respects at Blessed Rother’s grave site, said. “It was easy to share their excitement. What a great honor this will be for COF to have one of our members to be named a saint.”

Article by Katlyn Pischel

Thank you to HCR David Huber, Fr. Don Wolf (St. Eugene Catholic Church, Oklahoma City), Most Reverend Eusebius Beltran (Archbishop Emeritus of Oklahoma City), Holly La Vine, Fr. Samuel Schneider (Diocese of Superior, Wisconsin), María Ruiz Scaperlanda, Jim Wittrock (Oklahoma High Court), Frederick Krueger (Sacred Heart 1813, Oklahoma City), Carla Hinton and Paul Folger for their time and insight. Photos are courtesy of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City.

1‘He needs a miracle’ (oklahoman.com)

To watch Oklahoma Martyr, visit videos.oeta.tv/video/3007561328/.