Fr. Casimir Michael Cypher OFM, Conv., was a son, brother, Franciscan friar, Catholic Order of Foresters member, poet, missionary, and martyr. His life was not supposed to end in Honduras 46 years ago.

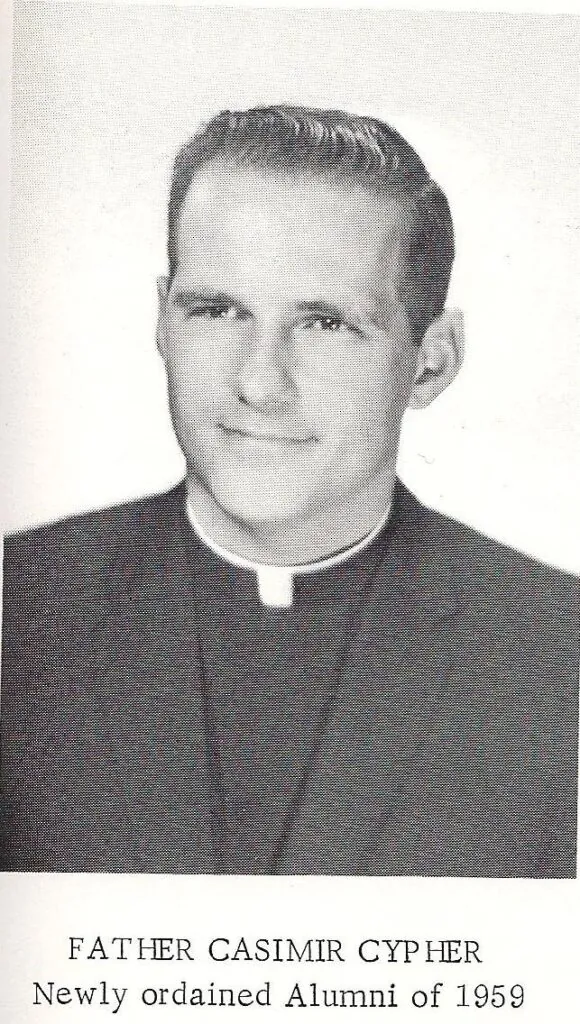

To know him was to know grace, and to witness him was to witness a modern-day St. Francis of Assisi. Born in 1941 in Medford, Wisconsin, Michael Jerome Cypher left after eighth grade to study at a Conventual Franciscan minor seminary. He had eight brothers and three sisters. They were a Catholic Order of Foresters family. Later, in 1959, he went to Lake Forest, Illinois, and took the name “Casimir.”

After a stint serving at a Franciscan parish in Hermosa Beach, California, Fr. Casimir was called to Honduras. He arrived in October 1973 to begin working in remote villages scattered among the mountains of Gualaco in the Honduran department of Olancho. Although he never fully grasped the native language, his warm personality made up for his struggle to communicate verbally.

Dr. Mike Gable, a professor of theology at Xavier University and former lay missionary who worked with Fr. Casimir in Honduras, recalled the Franciscan’s early mission work in Gualaco. “His job was to go out on horseback and visit the villages that were part of our huge parish,” Dr. Gable said. “He would go with saddlebags and give Mass in homes.”

For weeks, Fr. Casimir would go up into the mountains before returning to Gualaco. When he returned after enduring the rugged terrain, he would relax and tell stories by candlelight with Dr. Gable. “We shared a room, and he liked to do art that I was impressed with. He showed me some of his poems and I thought, ‘Wow, this guy’s got some Franciscan spiritual depth that is just impressive.’ He really had a spirituality that was far advanced,” said Dr. Gable. “We’d stay up and talk and tell funny stories. He often spoke about his mother Elizabeth and how she kept their Catholic family tight in their faith.”

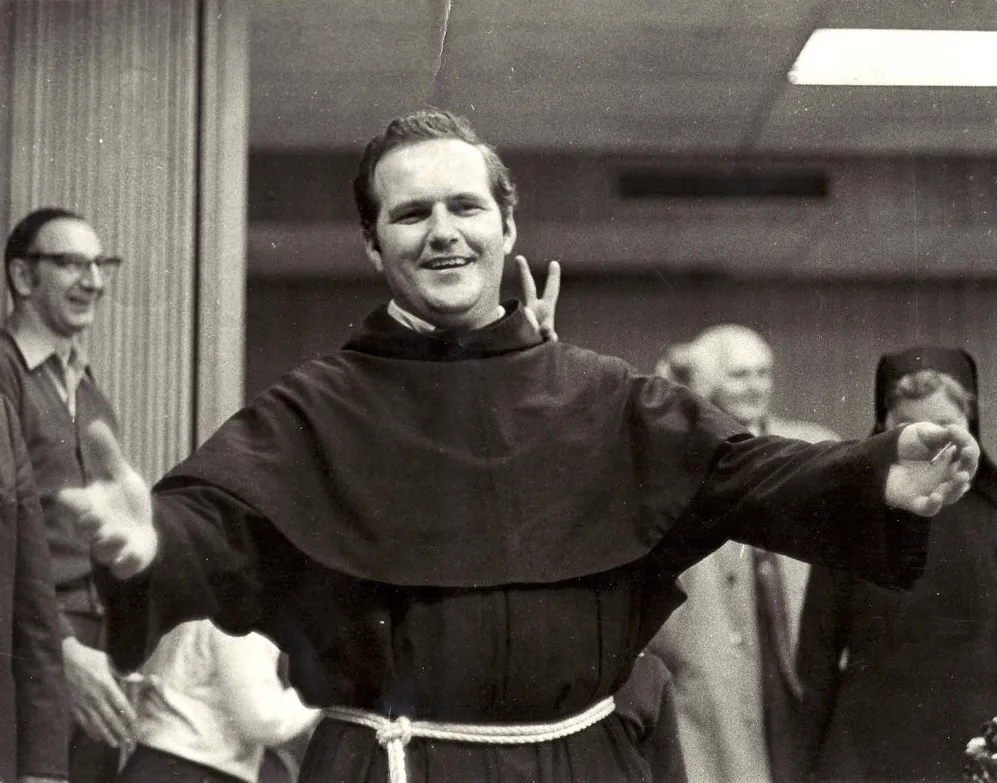

Throughout his life, Fr. Casimir had a reputation of being carefree and generous. But when he sat down to write, he was anything but carefree. His best work, a poem called “The Sun,” has stuck with Dr. Gable since the moment Fr. Casimir showed it to him in Honduras.

“It was written for Juanita Klapeke, a missionary from Louisville, Kentucky, who really struggled with the rough cowboy culture in Honduras. Things were falling apart for her, so she decided that the work was not for her,” said Dr. Gable. “She was disappointed, so Casimir wrote a beautiful poem called ‘The Sun’ to let her know that she could be the sun to people no matter where she was, just by using her love for others. He carved the poem into a mahogany plaque and gave it to her.”

At Fr. Casimir’s memorial Mass in Rockford, Illinois, Juanita read “The Sun.”

“She barely made it through,” said Dr. Gable. “About five years after Casimir died, I found out that Juanita was dying of cancer when her parents invited me to read the poem at her funeral.” Dr. Gable paused and took a deep breath. “That was really hard to do.”

After serving in Olancho, Fr. Casimir was stationed in San Esteban. Friar Mark Weaver, a Conventual Franciscan who served in Honduras after Fr. Casimir, said Casimir began repairing the church in San Esteban himself, a choice characteristic of his action-oriented approach to his ministry.

He did more than just physical labor, he was an advocate for education and the promotion of vocations. In early 1975, he wrote to his provincial office: “We’re trying to help the kids get to high school and promote vocations to the priesthood and religious life. Since people here are poor in all aspects, it’s a little tough. We’re always short of funds.”

Letters that he wrote home show that he suffered a great deal in Honduras. In August 1974, he wrote to his friend, “I’ve been sort of sick for a while—physically, mentally, and spiritually.” This was no exaggeration. Five months later, he suffered an infection in his bloodstream that required swift medical intervention in the U.S. During his time back in the states, he spoke in California and opened up about his struggles in Honduras. In that moment, perhaps he let himself be vulnerable. “God let me find out how weak I was,” he said. Nevertheless, he flew back to an increasingly unsafe Honduras soon after.

The heated political environment there was no joke: the Honduran military government and rich landowners felt threatened by the Catholic Church’s work in social justice, including its involvement in a new democratic political party. “The peasants,” according to a 1975 New York Times article that covered the political tension, “live on bare subsistence levels and make up 87 percent of the country’s three million people.” They were calling for sweeping reforms.

Although Casimir was not politically involved, in part because he lived far from the big cities in Olancho, the mere fact he was a priest put his life in danger.

Prior to his final journey to Honduras, Dr. Gable, who has since returned to the U.S., pleaded with Casimir to remain in the states. Casimir replied, “I can’t abandon my people at this time. I know there’s trouble, but I have to go back.”

“He made a choice to go back knowing that things were not going to get prettier or easier,” Dr. Gable said. “To me, that’s the mark of sainthood.”

One day in the summer of 1975, Fr. Casimir was driving his red Dodge pickup truck into Juticalpa, the capital city of Olanco. Sources differ on the reason he was going there. Some claim he was delivering a package. Others say he was driving a sick parishioner to the city hospital. One source thinks he was going to get his truck repaired. What no one disputes, however, is that hours earlier in Juticalpa, a platoon of soldiers and teachers and grade-school children had rushed into a building and massacred a group of farmers. Casimir, unaware of the slaughter, was driving straight toward the scene of the crime.

For reasons unknown, Casimir is said to have exited his vehicle in Juticalpa. Somehow, he was quickly apprehended by the soldiers and taken to jail. After he was questioned and tortured, the soldiers killed him and threw his body into a well. Some have speculated that his death was a case of mistaken identity because there was another priest in Honduras named Michel who was more politically active than Casimir. The soldiers, the theory goes, saw the name “Michael” on Casimir’s ID and mistakenly thought he was their target.

Although he is gone, Fr. Casimir’s legacy lives on in the lives he touched. “It’s a blessing to say that I knew a person who was very much like Jesus,” said Dr. Gable.

Article by Connor McEleney and Nick Sentovich